When I first saw Zhao Ziyang up close in 1987, he had just become the new party chief at the closing ceremony of a landmark Communist Party congress.

Zhao seemed on top of his game: relaxed, confident and poised to break the old Communist mold. Inside the Great Hall of the People, he walked around an elongated U-shaped table, set up for a “cocktail reception” for Chinese and overseas media. Under the glare of TV cameras, he answered our questions freely. Looking dapper in tailored Western-style suits, he contrasted sharply with dour Communist leaders dressed in gray jackets. Zhao Ziyang is fondly remembered as one of the pioneers of the reforms initiated by his mentor, Deng Xiaoping. Says University of Pittsburgh Prof. Tang Wenfang: “He was a pragmatic leader and was very successful in provincial-level market reforms in the late 1970s and early ’80s.” As provincial governor in Guangdong and Sichuan, he was credited for streamlining bureaucracy and boosting farm production. “If you want more grain, look for Zhao Ziyang.” So went a popular ditty. Noticing his successes, Deng Xiaoping plucked him for bigger jobs in Beijing. When he became premier in the 1980s and later the party chief, he stood out even more for trying to push equally bold political reforms. He advocated separation of the party and government affairs and “toumingdu” (transparency), his version of Gorbachev’s “glasnost.” Zhao may be faulted for going way ahead of the curve–the same mistake committed by his predecessor, Hu Yaobang. In 1987, Hu was fired by Deng Xiaoping for pushing policies deemed too soft toward “bourgeois-liberal ideas” and tolerating student protests. Two years hence, Zhao awaited the same fate.

Don’t Miss

Special: China

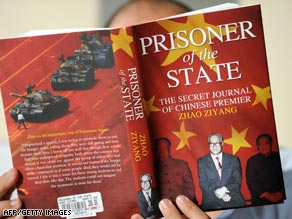

When Hu Yaobang died of illness in April 1989, thousands of students gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square to pay tribute to the reformist leader. In the weeks that followed, the student movement snowballed into a huge protest against corruption and call for freedom and democracy. Zhao apparently clashed with conservative old guards for his sympathetic stance toward student demonstrators. He was last seen in public in May 1989 when he visited student hunger strikers at Tiananmen and begged them to leave the Square. “I have come too late,” he tearfully told them. Behind him stood Wen Jiabao, then chief of staff of the Communist Party, who would later become China’s prime minister. That year, Zhao was purged from his party posts and accused of “splitting the Communist Party.” Admirers praised him, some equivocally. “Zhao Ziyang was a daring and resolute reformer,” said Zhai Weimin, one of the student leaders of the 1989 protests. “But he did not play the political maneuverings as well as other leaders. Otherwise, China would have been different now.” Other analysts say Zhao had little chance to succeed. Tang Wenfang explains: “He was caught between two trends. The hard-line conservatives were not ready for market reforms, so they resisted his policy initiatives. On the other hand, the ordinary people were not ready to absorb the painful price of market reforms: inflation, unemployment, corruption, all those negative unintended consequences of market reforms. So he faced resistance from both fronts.” Deng Xiaoping replaced Zhao with Jiang Zemin, the former Shanghai mayor who went on to lead China through 13 years of stunning economic growth before stepping down as party leader in 2002. For years after his ouster, Zhao remained a thorn in the government’s side. He remained a party member, and he was never formally charged with any crimes. Still, he was put under house arrest in Beijing. He was rarely allowed to step out, except to play occasional rounds of golf. Out of sight and out of power for half a generation, Zhao remained steadfast in his reformist program. In 1997, he wrote a letter to the Communist Party leadership calling for reform, saying that it should start with reversing the wrong verdict passed on the June 4 protests and the political rehabilitation of those who took part in it. The publication of Zhao’s memoirs, “Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang,” raise hope that there will be a revival of public interest in and debate over what happened in 1989. The memoirs are co-edited by Bao Pu, the son of Bao Tong, a former top aide to Zhao who continues to live under tight government supervision after being arrested and sentenced in 1989. Watch Bao Pu talk about what the memoirs reveal about that time » June 4 will mark the 20th anniversary of the bloody crackdown of the protests in Beijing. This has prompted China’s security forces to be on high alert to foil attempts to commemorate the date in public places like Tiananmen. Even so, a Chinese official who requested anonymity believes Zhao’s memoirs will have minimal impact in the mainland. “China has changed so much since June 1989,” he said. “Most Chinese are more interested in pragmatic day-to-day affairs, like finding jobs, making money, improving their lives, instead of political or ideological issues.”

Indeed, when former Chinese premier died in January 2005, he was a half-forgotten symbol of the reform era of the 1980s. The Chinese media did not even mention that he was once a leader of China. Beijing’s leaders hope to keep it that way.