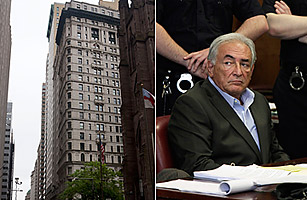

A week after former IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn posted a $1 million cash bail and a $5 million bond, he was moved from temporary lodgings on lower Broadway to a large townhouse in Tribeca. Unlike a large apartment building, a townhouse has no doorman, but for DSK, there is no need. Keeping watch over him will be multiple “armed monitors” courtesy of security firm Stroz Friedberg.

By the terms of Strauss-Kahn’s bail order, filed with the New York State Supreme Court on May 20, DSK is “confined to home detention 24 hours per day at an address in Manhattan.” He is permitted to leave the home only for court appearances, medical and legal appointments and religious observances, and the court must have six hours notice.

The people responsible for ensuring Strauss-Kahn’s compliance work for Stroz Friedberg LLC, a cyber security and computer forensics firm. According to “in-home detention protocols” prepared by the company, Stroz Friedberg employees will monitor Strauss-Kahn 24 hours a day, maintain a log of all visitors, search all visitors for weapon and have sole discretion to limit the type and number of visitors to DSK’s residence, along with any other measures that “may be required to prevent flight.”

This isn’t the first time Stroz Friedberg has kept watch over a high profile client awaiting trial. In 2009, the company provided bodyguards for disgraced financier Bernard Madoff. But in an interview with TIME, Ed Stroz, the firm’s founder and co-president, made sure to emphasize that guarding wealthy defendants on bail and making sure they don’t flee is not the firm’s “core expertise,” but rather a sideline business that coincidentally presented itself.

In 2000, Stroz, a former FBI agent who headed Bureau’s New York computer crime squad, teamed up with Eric Friedberg, an Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, who prosecuted computer crimes. “We figured ‘let’s see how this goes and let’s be nimble enough to adjust to the market place,'” says Stroz. “What the hell did we know? We were coming out of the government.”

They quickly expanded from consulting into investigations, building a computer lab to work with client data. Business scandals were their bread and butter: they investigated accounting fraud allegations at Kmart and AOL, conducted forensic accounting and digital surveillance in the ashes of the Enron collapse and in general tried to tackle “huge problems that revolved around minutiae,” according to a Harvard Business School case study on the company. But they never lost their gun-slinging side either, as even computer crime work requires a private investigator license in many states. Along the way, the firm, which has grown to nine offices worldwide, began providing testimony in criminal trials — they were the government’s computer forensics expert in the Martha Stewart prosecution regarding the collection and authenticity of electronic evidence in the case. It was their contacts with litigators and private investigation services that got them assignments to do high-profile private security.

“I don’t think we’re going to get into designing women’s shoes or anything like that, but it is a natural extension to be able to do these services correctly, to draw from the legacy skill sets we have as investigators and former agents, combined with the power of how digital evidence affects this mission,” says Stroz somewhat cryptically.

Although the Strauss-Kahn case has kept them in the news, Stroz sees digital and cyber security as the most important growth area for the firm in the coming years. “This is going to sound grandiose, and I don’t meant it to,” Stroz says, “but we’re kind of evolving into the firm you have to have if you’re a serious industry out there. Who isn’t at risk for litigation, regulatory scrutiny, trade secret theft, insider problems? And when that happens, that is not a normal business issue. And you don’t get good at this unless you’re kind of a jungle cat out there seeing things.”

See pictures from the career of Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

See TIME’s Pictures of the Week.