Cell phone technology is helping developing nations prepare for disease threats such as a new strain of swine flu, an outbreak of measles or the increased spread of HIV.

Kenya proved it in 2007, when the East African nation suffered its first case of the polio virus in more than 20 years, said Yusuf Ajack Ibrahim, a health care worker at the Kenyan Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. As thousands of Somalis fled to Kenya to avoid violence in their homeland, the exodus sparked a serious health crisis, Ibrahim said. “One case of confirmed wild polio virus put at risk the lives of 100,000 children,” he said. Kenyan health officials determined that they needed a way to quickly survey and assess the situation and initiate a massive immunization campaign. The solution was on the Internet, where they found a free, open-source application designed for personal digital assistants, called EpiSurveyor. Open-source software is posted online for anyone to use and alter to suit their needs. Downloading the software to cell phones enabled officials to gather data directly from the site of the outbreak and send it electronically back to headquarters for faster analysis. This cuts down on the time officials have to spend collecting paper surveys and analyzing them individually before they can begin treating people. “The information gave us useful feedback not only on the affected area but on the neighboring ones as well and helped us put plans and measures in place to stop the spread of the virus,” Ibrahim added.

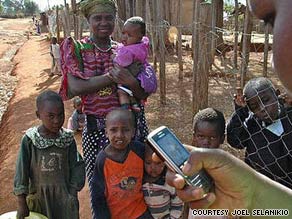

Don’t Miss

In Depth: Edge of Discovery

Physician and epidemiologist Dr. Joel Selanikio predicts that within a year, health officials will be using the technology to track other threats in developing nations, such as the recent Mexican swine flu outbreak. Selanikio invented EpiSurveyor in 2003, after he and American Red Cross technologist Rose Donna began searching for a more efficient way to gather data on immerging diseases. They started a nonprofit organization, DataDyne, aiming to use mobile devices to efficiently and immediately gather public health information. “Collecting data on paper and then taking two years to enter the data is a tremendous drain and barrier to good public health,” said Selanikio, who teaches pediatrics at Washington’s Georgetown University Hospital. Mobile devices such as PDAs or handheld computers have been used for field studies since the late 1990s, but electronic survey methods have traditionally been expensive, labor-intensive and challenging to implement on a global scale. Many global health institutions are now encouraging the use of advanced methodologies such as smart phones and open-source software as the next generation of data transmission, said Dr. Ramesh Krishnamurthy, an informatics scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. EpiSurveyor frees health care workers from hiring programmers to create electronic surveys. Data gatherers can customize their questionnaires online, download the questionnaires onto a cell phone that has Internet capability, poll patients and do direct analysis, all through a touch pad on a cell phone. Ibrahim credits the technology with saving Zambians who were threatened by a frightening outbreak of measles in 2007. The government didn’t know that vaccine supplies were low, he said. Using EpiSurveyor, health care workers discovered that 60 percent of their vaccine stockpiles in remote areas were missing. They mobilized a response within three weeks, he said. “Imagine if we have an outbreak of measles and the information is relayed to us three months after the outbreak. By the time we respond, lives would have been lost, but if we can get the information in a day or half a day, we an mount a quick response,” Ibrahim said. “By being able to relay the information at an appropriate time, that — in and of itself — is life-saving,” he added. Fans point out that EpiSurveyor’s success hinges on ready access to technology already in place. “There are 4 billion mobile phones in the world; 2.2 billion of those are in the developing world,” said Claire Thwaites, who heads a partnership between the U.N. and Vodafone, which funded EpiSurveyor. Sixty-four percent of all mobile phone users live in the developing world, according to a U.N. estimate. By 2012, the U.N. believes, half of all residents in remote areas of the world will have mobile phones. Compare mobile ubiquity to the 305 million PCs or 11 million hospital beds in the developing world, Thwaites said. The potential for mobile technology to help manage health care is huge, she said. With the help of the U.N.’s World Health Organization and government health officials in more than 20 African countries, more than 800 health care workers are now trained to use this cell phone software, revolutionizing the way health care data can be collected, monitored and assessed.