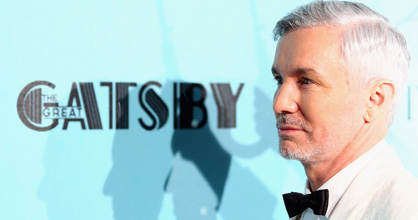

Baz Luhrmann is temporarily lost for words. It’s possibly jet lag from two weeks of traipsing from New York and London to Cannes and Sydney, or maybe this is a question he hasn’t heard before.

Finally, the dapper 50-year-old wizard of Oz film-making, born Mark Anthony Luhrmann, lights up and delivers his verdict on the Kiwi connection involved in his latest project – an adaptation of F Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby – Wellington-born cinematographer Simon Duggan.

“There was a period that I was really thinking about digital and 3-D and I met a few DPs [directors of photography] at the time. I saw his work and thought he would know digital because he’s been working in it from very early days [Duggan’s credits include I, Robot and instalments of the Underworld, Die Hard and The Mummy action movie franchises].

“But meeting Simon you think he might be the least likely person because he was extremely reserved and very quiet and very gentle. I just looked at him and absolutely went on instinct. At a certain point, you ask yourself if you connect with someone, and I thought this would need someone like Simon, who was meticulous and kind of absorbed.”

Known for a signature, almost operatic film-making style of visual and aural excess, most notably in his Red Curtain Trilogy of Strictly Ballroom, Romeo + Juliet and Moulin Rouge, the father of two (Lillian, 9, and William, 7) has added an extra level of complexity to his Gatsby – 3-D.

Why touch a format that many cinema-goers still have plenty of reservations about

“Early on James Cameron was showing me what he was doing on Avatar but it was watching the original reels of Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder that swayed me,” admits Luhrmann. “I could see it was an actor’s medium and it got me thinking, ‘gee, if I could see my five main actors tearing each other apart in a room emotionally in 3-D, what would that be like'”

He also cites Gatsby’s author as inspiration for pushing the envelope. “Fitzgerald was a great lover of modern techniques and at one stage put lots of cinematic devices in his books. I found myself wondering if he would turn away from a new tool, new device like modern 3-D.”

So will 3-D be the new Baz Luhrmann standard “I loved it and I didn’t find it very difficult to deal with at all. Would I make everything in 3-D It’s got to be horses for courses, but I would love to do more stuff with it. I’ve seen television where you don’t even need the glasses.

“It’s like when sound came along. In The Jazz Singer, they only had the songs in sound because no-one wants to hear an actor speak. Sound ruined movies, initially. It killed a lot of careers and it took a long time before it was used creatively, because sound technicians thought people couldn’t talk over one another.”

Aural creativity is something Luhrmann prides himself on. As Moulin Rouge and Romeo + Juliet show, he puts together soundtracks that capture a film’s emotional beats, especially via their lyrics, rather than strictly adhering to period authenticity. No surprise, then, that his Gatsby includes 21st century tracks by Florence and the Machine, Beyonce, Jack White and Lana Del Ray.

Ad Feedback

“Early on I made the decision that since Fitzgerald put Afro-American street music front and centre in his novel – the jazz of the moment – I would put the pop music of the moment in my film.

“Then I hooked up with Jay-Z, who is a great collaborator. I really like him and we’ve come to socialise a bit. I brought some stuff to the table with Anton Monsted , produced some stuff myself, and worked very closely with Florence who is a friend of mine – I saw her for a wild night in London a couple of nights ago – that girl! Flo slow down!” he mock chides, clearly enjoying the memory of an evening that might still be taking its toll on him. “The xx is a wonderful young band, Jay did all the rap stuff and the Bryan Ferry Orchestra were releasing their jazz album so we jumped on that.”

While some may see the modern soundtrack as a cynical attempt to woo younger audiences to this near century-old tale of infidelity, murder and quixotic passion, Luhrmann is adamant his Gatsby isn’t aimed at any particular generation. “I just had the epiphany on the book about a decade ago that it was us – now. Then in the crash of 2009 I just went ‘I’d be insane not to do it because the book was written for this kind of period’. There was a terrorist attack on Wall St [a horse-drawn wagon bomb allegedly planted by Italian anarchists in September 1920 – although the culprits were never caught] at the beginning of the 1920s, then the stock market rose. There’s just this amazing hubris, mirroring the time we were in recently.”

Describing Gatsby as “the American Hamlet” [“it might be a portrait of the jazz age that’s also a cautionary tale regarding the American dream, but it’s a universal tale that can play anywhere, anytime, anyhow”], Luhrmann says solving the problem of the story’s internal monologue (the story is told from the perspective of a traumatised Nick Carraway, befriended by the charismatic Jay Gatsby and cousin of Gatsby’s obsession, Daisy Buchanan) was his biggest task. It’s the reason why only three previous cinematic attempts have been made – a 1926 now-lost silent movie, a 1949 version with Alan Ladd, and the Robert Redford-headlining 1974 film which boasted a screenplay written by Francis Ford Coppola.

After considering having Carraway confessing to a priest a la Amadeus, Luhrmann says he found the answer supplied by Fitzgerald himself. “In the notes for The Last Tycoon he mentions how he wanted to put the character in an asylum. Then myself and Craig [Perkins, Luhrmann’s regular screenwriting collaborator] met this wonderful character called Walter Menninger, who brought psychoanalysis to America. He psychoanalysed Tobey Maguire [who plays Nick] in character.”

No doubt Luhrmann would make a fascinating psychoanalytical study, but everyone involved in Gatsby, from Maguire to co-stars like Carey Mulligan and Joel Edgerton, and Luhrmann’s creative and life partner, Catherine Martin (as well as a 15-year marriage, the two have also collaborated on all his films, with Martin acting as both a production and costume designer), are effusive in their praise for the director and the man, describing him as a generous host, both on and off set. Actors in particular seem to love him, perhaps because he identifies with their struggles. Rejected initially by NIDA, Australia’s prestigious drama school, in 1980, Luhrmann rose to the heights of a guest run on Aussie soap A Country Practice before finding his calling, first on the stage and then in the director’s chair.

He’s a great lover of classic Hollywood cinema, something instilled in him by his father, who not only owned the petrol station in the small New South Wales town of Heron’s Creek, but also the movie theatre. You can see that love in all Luhrmann’s films, but if his much-maligned 2008 epic Australia was a little too Gone With the Wind, this has just the right amount of Citizen Kane, from its rise and fall storyline, the main character’s attempts to link with the past, its recounted-tale style and the deep-focus cinematography.

“Yeah, there’s a bit of Kane in there, because I think Kane and Gatsby share some similarities,” admits Luhrmann. “But there’s also a bit of Casablanca and a bit of a wink to Billy Wilder in the pool scene. I’m hooked on those older films because they’re both artificial and emotional. Big ideas expressed poetically.”

It’s a way of cinematic storytelling Luhrmann himself seems single-handedly intent on keeping alive.

Great Gatsby (M) opens in New Zealand cinemas on Thursday.

– Your Weekend