As bright spring days gradually turn hot and muggy, the consensus in Damascus is that the protest movement has been badly burnt. The activist Facebook group Syrian Revolution 2011 put out an order for a general strike across Syria on Wednesday calling for “mass protests” and the closure of all schools, universities, shops and restaurants, “not even taxis.” But there was no apparent strike on Wednesday morning in central Damascus.

The mucky market was bustling with veiled women shopping for groceries and plucky boys in tattered jeans shouted out prices for their wares. Battered yellow taxis swiveled past large green buses brimming with kids in school uniform, their brows sweaty and their eyes filled with boredom. Damascus had resumed its regular life, seemingly oblivious to the fact that Syria has been the focus of the world’s attention for over two months.

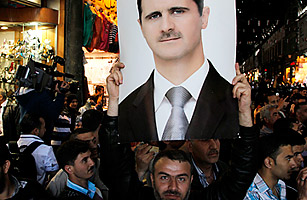

Syria’s government has cracked down ferociously after demonstrators — bolstered by the ouster of both the long-ruling despots in Egypt and Tunisia — called for the end of president Bashar al Assad’s regime. On Wednesday, after long prodding, the U.S. slapped sanctions on the Assad government for human rights abuses. Washington’s actions may be too late — if sanctions had any chance for success at all.

The demonstrations in Egypt and Tunisia were bolstered after police and army brutality increased sympathy for the protesters, inspiring thousands more to flock to the cause. It is not the same in Syria. Even as the government repression grew uglier, most sources reached by TIME report that the turnout for street protests is significantly smaller than in past weeks. The fear among anti-government sympathizers is that the violence in Syria appears to be working. In an interview with the Syrian newspaper al Watan published on Wednesday, Assad said that Syria has now “overcome the crisis.” On the streets of Damascus, many say they agree.

Indeed, many activists are either in prison or too scared to assemble. Sports stadiums and government buildings are being used for improvised prisons as police arrest thousands of protesters, according to Syrian human rights organizations. A Syrian student, who said two of her classmates have gone missing, told TIME that anyone either protesting or documenting the demonstration risks arrest and torture. “You could be walking along the street and never get to where you’re going,” she says, chuckling slightly, as if the horror of her statement was only tolerable in jest.

Syria’s ubiquitous secret service has always been effective at tapping calls, employing neighbors to spy on each other and reading emails. A Korean student who studied Arabic here says that during a long phone call he had with his parents back in Korea the line went dead and a gruff man’s voice cut in. “Speak in English, please,” the mysterious voice asked politely.

Observers here say the regime has fostered a culture of paranoia to deter people from further civil disobedience, contributing to Wednesday’s failed strike. During the recent tumult, unprecedented numbers of people went missing — around 8,000 according to local human rights groups — and activists are petrified to communicate over the phone.

Widespread fear has made it impossible to judge the mood among Syrians. Talking politics is taboo and speaking out against the regime can lead to jail time. Many people say they fear the unrest could cause sectarian strife, such as in neighboring Lebanon and Iraq. Some middle-class Syrians say they fear losing prosperity brought by the president, who opened the country to foreign investment when he ascended to power in 2000. If the president fled, they say, the economy would be crippled by populist demands for socialist policies.

A Syrian journalist, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal, said such pro-government rhetoric is mostly lies told by people to protect themselves. “Everyone hates the government, everyone. They are just too scared to say it,” she said when asked why people continue to say they support the government. She believes that the anti-government movement, now battered and bruised, is weighing whether it is feasible to continue to protest when the military is willing to use live ammunition consistently against demonstrations. “I don’t think the President will leave anytime soon, but nobody wants what is going on now.”

For those still demonstrating, violence is guaranteed. Armed with anything from wooden batons to assault rifles, the plain-clothes secret police, or mukhabarat, have set up positions in key areas around the capital preventing many protests from even starting and augmented security measures confine people to their neighborhoods, or even their houses.

Radwan Ziadeh, Washington-based Syrian dissident and visiting scholar at the Institute for Middle East Studies at George Washington University, says state security is much more brutal than that of Hosni Mubarak, the ousted President of Egypt. “[The Assad government] has a lot of experience with brutality,” he told TIME. Western observers in Damascus agree that the extensive use of indiscriminate violence from the start of the uprising in Syria has managed to deter many from joining the protests. Human rights groups say that between 700 and 850 people have been killed so far.