In the 76-year history of the New York Film Critics, only two moviemakers have been honored with life achievement awards: Jean-Luc Godard and Sidney Lumet. The French director is of course the prickly master of movie modernism, but Lumet was something Gotham critics could appreciate: the primary apostle of streetwise cinema, the torch-bearer of ground-glass realism and, for a half-century, the ultimate chronicler of New York City in all its agita and chutzpah.

Though he shot films in Boston, Chicago, Toronto, London, Paris, and in Texas, New Mexico and Louisiana , Lumet made his name investigating the rough edges of the city he grew up and old in. A fat fistful of his New York films — 12 Angry Men, The Pawnbroker, Bye Bye Braverman, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, Prince of the City, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead — could serve as a time-capsule of the American metropolis in its violent grandeur, its cunning, desperation and raw wit. Let Woody Allen send valentines to the upper-middle class of neurotic literati. Lumet’s films were more like ransom notes, third-degree confessions, anguished screams through the bars of a highrise window — from his Network — that “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more.”

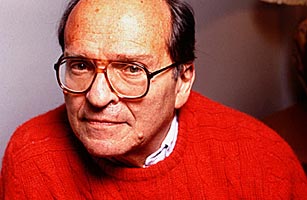

As driven, aggressive and purposeful as any of his film protagonists, Lumet directed 43 feature films from his 1957 debut, 12 Angry Men, to the 2007 Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. Nominated four times for the Best Director Oscar, and receiving an honorary Academy Award in 2005, Lumet finally ran out of stories, clout and boundless creative energy. He died April 9, at 86, of lymphoma at his Manhattan home.

What Andrew Sarris wrote in The American Cinema of George Cukor, that his “filmography is his most eloquent defense,” applies equally to Lumet. If you add to his New York films his work in a wide variety of genres — powerful versions of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night and Chekhov’s The Seagull, the anti-nuke parable Fail-Safe, the Brit cop film The Offense, the Agatha Christie all-star romp Murder on the Orient Express, the Boston-set courtroom drama The Verdict and the 1968 documentary King: A Filmed Record… Montgomery to Memphis — you’re likely to wonder: did one man direct all those movies?

Part of the answer is that he worked with some of the finest writers in the endangered species of social drama. He made films from the works of Tennessee Williams, John Le Carre and Larry McMurtry; he shot scripts by Paddy Chayefsky, David Mamet, Herb Sargent and Gore Vidal, and by movie-scenario stalwarts Reginald Rose , Sidney Buchman < The Group>, Walt Salt and Norman Wexler and Frank Pierson . They provided Lumet with fierce characters and the kind of fiery oratory that actors love to deliver. His job was to get the heat on-screen.

He so often succeeded because, when stars wanted to be actors, they came to Lumet. In just his first five films — 12 Angry Men, Stage Struck, His Kind of Woman, The Fugitive Kind and Long Day’s Journey into Night — he directed Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, Sophia Loren, Marlon Brando, Anna Magnani, Joanne Woodward, Katharine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson and Jason Robards. Later, he freed Sean Connery from his James Bond indenture ; he unleashed Al Pacino’s holy madman ; he steered Peter Finch, Faye Dunaway and Beatrice Straight to acting Oscars in Network. He got Richard Burton to sober up for Equus and Michael Caine to play a bisexual killer in Deathtrap. For Murder on the Orient Express he persuaded a dozen top stars — including Connery, Ingrid Bergman , Lauren Bacall, John Gielgud, Anthony Perkins, Richard Widmark and Vanessa Redgrave — to work for peanuts just because it would be a lark to be among one another, and because Sidney asked them to.

He knew actors because he was practically born one. Lumet started at four in his father Baruch’s Yiddish theater troupe on the Lower East Side and appeared in the original stage production of Sidney Kingsley’s Dead End when he was 11. After World War II service in India and Burma he joined the fledgling Actors Studio, only to be tossed out. So he started his own company, and at 22 was a director on Broadway. Yul Brynner, then a director, got him into live TV drama; in a 2005 Turner Classic Movies interview with Robert Osborne, Lumet recalled the blessing of being in an infant medium — “Nobody knew what they were doing, so there was nobody to say No.” Building a renown for goading actors toward self-revelation, he caught the attention of Fonda, who was producing a movie version of Rose’s jury-room TV play 12 Angry Men. For the nameless jurors Lumet rounded up Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall, Jack Warden, Jack Klugman, Ed Begley and brought sizzle to the confrontation of principal and prejudice. Vote for the world’s most influential people in the 2011 TIME 100 Poll.