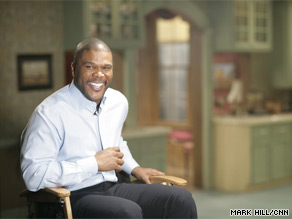

Tyler Perry is known today as the first African-American to own a major film and TV studio. He’s a pioneer whose own life story is a rags-to-riches tale that reads like a screenplay.

Now a writer, actor, director and producer — Perry’s success grew out of a troubled home in a poor neighborhood in New Orleans, Louisiana. Strong on faith, Perry named his first play “I Know I’ve Been Changed,” after an old Negro spiritual. It was a gospel musical about two adult survivors of child abuse. In 1991, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he worked as a bill collector and eventually scraped together enough money to rent a small theatre and stage the play. With only 30 people in the audience, the play was a flop. For the next several years, he struggled and was often broke and sometimes lived in his car. But Perry refused to give up. He finally got a second chance in 1998, when a promoter booked the show in the Tabernacle, a former church turned concert hall in downtown Atlanta. It was a sold out hit and the little boy from inner-city New Orleans was well on his way. Perry then took his plays on the road and traveled the so-called “chitlin’ circuit” to theaters in Memphis, Tennessee, Detroit, Michigan, and Baltimore, Maryland — where black entertainers historically performed for predominantly black audiences. He began making a name for himself with African-Americans. In 2004, he started looking for backers for his first movie project “Diary of Mad Black Woman,” a story about a devoted wife in a bad marriage. He said he faced a wall of ignorance when he pitched white executives in Hollywood. One told him the project was doomed to fail at the box office because the core audience for Perry’s stage plays — black churchgoers — wouldn’t go to the movies. Another said the dialogue for his characters was unrealistic. Though he was largely unknown to white audiences, Perry refused to play by Hollywood’s rules and demanded creative control of his projects. Tour of Tyler Perry’s back lot »

‘Black in America 2’

Soledad O’Brien investigates what African-Americans are doing to confront the most challenging issues facing their communities. You’ll meet people who are using groundbreaking solutions in innovative ways to transform the black experience.

Tonight, 8 p.m. ET

see full schedule »

He was resigned to bankrolling the project himself and selling it as a DVD when he got a call from the independent studio Lionsgate. They struck a deal and he made “Diary” for about $5 million. The movie earned 10 times that at the box office. Since then, Perry’s movies have grossed nearly $400 million and he’s developed a loyal following. He now demands not only creative control but also ownership of the finished product. Still, it’s just the beginning, he said. “I don’t necessarily feel like I’ve arrived.” Even so, Perry has a prolific output of stories, including his movies “Why Did I Get Married,” “Meet the Browns,” “The Family that Preys,” and “Madea’s Family Reunion.” He signed a $200 million deal with TBS (owned by Time Warner, the same company that owns CNN) for 100 episodes of “House of Payne,” one of television’s most popular shows among black adults. The sitcom is now in syndication, making even more money for Perry. Perry said ownership of the finished product is key to building wealth, a principle he hopes other African-Americans will embrace. How are entertainment heavyweights changing black stereotypes “If you want to think about longevity,” he said, “if you want to think about your family and generations down the line, then you have to own it.” And own it he does. Tyler Perry Studios, on 30 acres in Atlanta, is his black Hollywood. But he is quick to acknowledge his debt to the legendary black actors from an earlier generation by naming two of his soundstages after Sidney Poitier and Cicely Tyson. He has also helped introduce them to a new generation by casting Tyson, 76, an Oscar-nominated actress, in two of his films. Tyson opens up about life, career » A study by the NAACP found that African-Americans are “underrepresented in almost every aspect of the television and film industry,” but Perry is able to hire on both sides of the camera. On his production crews, black employees are getting unprecedented career opportunities, and black actors are portraying characters beyond the predictable drug dealers and thugs. “What makes me feel great is to be able to pull up to this place and to be able to have 300 people working and running around, trying to get things done,” he said. “That makes me feel great.” His greatest accomplishment, he said, has nothing to do with business. “It’s more personal than that for me,” he said. “My biggest success is getting over the things that have tried to destroy and take me out of this life. Those are my biggest successes. It has nothing to do with work.”

Don’t Miss

Sound off: Changing black stereotypes in Hollywood

Perry sending rebuffed kids to Disney

In Depth: Black in America

The NAACP has honored Perry with its Image Award, but there are some who believe his characters don’t portray African-Americans positively. “He’s made a lot of money, but the quality of work is sorely lacking,” said Todd Boyd, a University of Southern California film professor and culture/media critic. Some of Perry’s characters rely heavily on exaggerated personalities and slapstick comedy. Boyd is particularly critical of Perry’s recurring character, Madea, an over-the-top grandmother who smokes marijuana and brandishes loaded guns she keeps in her purse. Perry himself plays the tough, buxom matriarch, who runs at full throttle fueled by country wisdom and ghetto strength. “It seems a bit ironic that at the moment of the first African-American president, the most popular African-American figure in the media is a man in drag engaging some of the most stereotypical images of African-Americans ever created,” Boyd said. Perry said his critics are missing the point. “They miss the messages of empowerment,” he said. “Sure, the silliness of ‘Madea,’ the silliness of ‘Brown,’ it’s broad, it’s over the top. Great. Fine. I get it. But how can you miss the message of forgiveness How can you miss the messages of empowerment “I would love to share with them the letters that I’ve gotten from people. ‘This helped me get through a tough time.’ ‘I was gonna commit suicide.’ ‘My husband and I weren’t speaking until we saw “Why Did I Get Married” It saved our marriage.’ ” For Perry, his work will always be about writing from his experiences, old and new.

“Whatever I’m experiencing in life is what I’ll write about,” he said. “I’m telling you, just to think this little boy from Louisiana can do it, anybody can do it.”