Ousted Honduran President Jose Manuel Zelaya stood a mere feet from his country’s border Friday afternoon, surrounded by supporters as he attempted to fulfill a vow to return nearly a month after being removed by a military-led coup.

Zelaya stopped about 100 yards short of the border and sat in his vehicle for several minutes under a strong rainstorm. It was not immediately known whether he would try to cross into Honduras any time soon. His arrival came minutes after police and soldiers fired on his supporters in the Honduran city of El Paraiso, across the border from the Nicaraguan town of Las Manos, where Zelaya stopped. Two people were wounded, CNN en Español Jorge Jimenez said. The police and soldiers fired tear gas at the demonstrators for about 15 to 20 minutes before letting off a barrage of 15 to 20 shots, Jimenez said. About 1,500 police and soldiers have faced off with Zelaya supporters in El Paraiso, about seven miles (12 kilometers) from the border with Nicaragua. The apparent shootings happened minutes after Zelaya held a news conference on the Nicaraguan side of the border and asked police and soldiers to let him back into his country. “Allow me to return to my country,” Zelaya said, directly addressing his nation’s police and army. “To embrace my fellow countrymen, my children, my wife, my mother.”

Don’t Miss

Ousted leader begins journey back to Honduras

New Honduran proposal on table

Zelaya to announce return to Honduras

EU suspends aid budgeted for Honduras

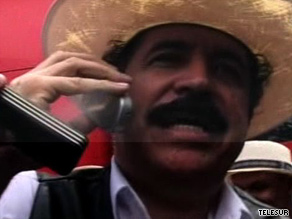

Provisional Honduran President Roberto Micheletti has said Zelaya would be arrested if he crosses over into the country. Zelaya, whom the military ousted June 28, led a convoy Thursday to the Nicaraguan city of Esteli, near the border with Honduras, and spent the night there. He left Friday morning in a 20-vehicle caravan to continue the trek toward the border. TV images showed Zelaya driving his own vehicle, wearing a white shirt, black vest and his trademark white hat. Micheletti warned Zelaya against attempting to return, saying that Honduras cannot be held responsible for any bloodshed that could occur. Honduran police and soldiers set up roadblocks between Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, and the border, and were preventing all buses from crossing through, according to news reports. Some Zelaya supporters in El Paraiso told Telesur they had taken back roads through the mountains to avoid the roadblocks. Salomon Escoto Salinas, the National Police director, said in a televised news conference that cars and people were being searched for weapons. “Our job is to maintain order of the people who are protesting,” Escoto Salinas said. “If there is any vandalism, the police will act and we will apply the laws.” Escoto Salinas declined to say in an interview with CNN en Español whether Zelaya would be arrested if he crossed into Honduras. The National Police has a plan, and it will be carried out, he said. The United States has asked Zelaya not to attempt a return. “Any step that would add to the risk of violence in Honduras or in the area, we think would be unwise,” Assistant Secretary of State Philip Crowley said Thursday. U.S. officials reiterated that request Friday. Zelaya told reporters Thursday night in Nicaragua he hopes border guards in Honduras will recognize him as president and commander in chief and put down their weapons when he attempts to cross. “We go with a white flag, with a flag of peace,” Zelaya said. Micheletti’s government announced a curfew Thursday in the border area from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. A less-restrictive curfew remained in effect in other parts of the country. The increasing tensions come after the apparent failure of a peace accord offered Wednesday by Costa Rican President Oscar Arias, who mediated two rounds of unsuccessful talks between the two sides. The document, dubbed the San Jose Accord, calls for Zelaya’s return to power, the creation of a unity government and early elections. The accord was similar to a plan Arias suggested over the weekend, but with more details and the creation of a truth commission to investigate the events that led to the crisis. The proposal also included a timeline for its implementation, which placed Zelaya back in Honduras by Friday. But Zelaya seemed intent to return on his own timeline, as neither side has signed the agreement. Hopes were slim that the agreement would be signed, as the Zelaya camp publicly said it rejected the document, and Micheletti’s side said it would have to seek approval from the other branches of government before proceeding. The Honduran Supreme Court has said it would not accept Zelaya’s return under any circumstances. On Thursday, the United States and Organization of American States expressed support for the San Jose Accord. “A favorable response to this proposal opens a path of reconciliation,” OAS Secretary General Jose Miguel Insulza said in Washington. “A rejection of this proposal opens a path toward confrontation. And I want to say very frankly, we don’t want a path toward conflict.” The Honduran political crisis stems from Zelaya’s desire to hold a referendum that could have led to extending term limits by changing the constitution, even though Congress had outlawed the vote and the Supreme Court ruled it illegal. The takeover has drawn international condemnation, including demands by the U.N. General Assembly, OAS and European Union that Zelaya be reinstated. Micheletti has rejected the characterization of the takeover as a coup, saying Zelaya’s removal was a constitutional transfer of power.