It was early one Sunday morning when the killer rang at a front door that was decorated with a wreath for Christmas. When his victim answered, he fired four fatal shots, ran off and disappeared.

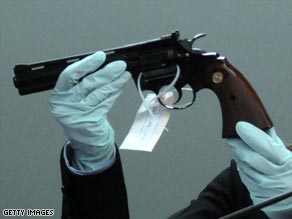

The unsolved murder of Marianne Wilkinson, 68, in a town near Dallas, Texas, in December 2007 has left investigators with few clues and few leads. They recovered the gun used in the crime a few months later, but the gunman’s identity — and his motive — remain a mystery. Now, a groundbreaking technique developed across the Atlantic Ocean in Britain may help Texas police and others to crack cold cases like this. The technique enables scientists to detect fingerprints on spent bullets and shell casings, even when the print had been wiped off. It works by detecting the minute corrosion of metal caused by sweat, which corrodes the metal in the shape of the fingerprint. “That sweat is in the pattern of the original fingerprint that was deposited,” said John Bond, a forensic scientist for England’s Northamptonshire Police and a researcher at the University of Leicester, who developed the technique. The corrosion is often impossible to see with the naked eye because it’s so small — as small as a micron, which is a millionth of a meter, Bond said. His method involves dusting the metal with a fine black powder that adheres to the corroded areas, allowing scientists to see the fingerprint. A detective from the police department in North Richland Hills, Texas, where Wilkinson lived in a gabled home with her husband, went to meet Bond late last year, Bond and the department said. Bond was able to obtain a print from the shell casings in the Wilkinson case, meaning police could be able to discern who loaded the gun, if they can find a match, North Richland Hills Police Investigator Larry Irving told CNN. Police are optimistic Bond’s technique will bring them another step closer to solving the case. “Prior to (the detective) coming over, and one of the reasons he came over, is they had little or no forensic evidence for this murder,” Bond said. “So my own feeling would be that finding fingerprints would be significant.” Investigators believe Wilkinson may have been the victim of mistaken identity, according to a profile of the case posted on the Web site for the television show “America’s Most Wanted,” which featured the case. A neighbor whose address is very similar to Wilkinson’s told police she had recently gone through a bitter divorce, and that she and her ex-husband had an ongoing business dispute, according to the Web site. Large amounts of money were at stake, the show said, and the woman believed she was the intended target. Investigators traced the gun’s history to a man who is now deceased and, authorities believe, had no connection to the slaying, according to the television show’s Web site. Police believe the gun has changed hands several times since then and are still seeking information on its latest owners. The bullet fingerprinting technique won’t necessarily solve crimes like the Wilkinson case but could unearth new clues, Bond said. “It’s helping police get evidence they didn’t have before,” he said. “It’s simply a new line of inquiry and can be especially valuable with cold cases.” In September, Bond found fingerprints on a shell casing from another murder case — a 1999 double homicide in Kingsland, Georgia. In that case, the suspect or suspects entered a Title Pawn business downtown, shot and killed the two employees and stole a small amount of money, said Kingsland police lieutenant Todd Tetterton. Police assigned a full-time cold case detective, Christopher King, to the case because of “some things that had changed.” The department read about Bond’s technique in a magazine article and contacted him to see if he could help, he said. “We were interested in trying anything we could,” Tetterton said. Four shell casings had been found at the crime scene, but fingerprint testing using traditional techniques didn’t reveal anything of use. Bond was able to find fingerprint ridges on three of the four casings, and one of them yielded enough ridge detail to possibly provide an identification, a University of Leicester statement said, quoting King. Tetterton would only say that more than one shell casing was found at the scene, and said Bond was able to get results for detectives. He declined to say more, citing the ongoing investigation. “The results are surprising,” the university statement quoted King as saying. “I feel very optimistic. These results are better than I had expected and better than I hoped for.” Bond doesn’t advertise his services, which he performs free of charge. “All of the inquiries we’ve had from the U.S. police forces have all been initiated by them,” he told CNN. “We never say no, so anybody who says, ‘I’ve got some shell casings, we have some over 30 years old’ — we always say send them and we’ll have a look.” Bond says he tries to know as little about a case as possible before he looks for fingerprints, so no one can accuse him later of looking for something specific. In one case, he said, he found a partial print on a shell casing sent in by police in Boulder, Colorado. The detective told him it was a fingerprint they expected him to find. “That was confirmation for me” that the technique worked, Bond said. The technique won’t work, however, if a person has just washed their hands or put on gloves before loading a gun. But Bond said that’s not too much of a concern. “Because of the nature of who these people are and the nature of what they’re committing, personal hygiene is not foremost in their mind when they’re doing this,” Bond said. “It’s also the heat of the moment. They might be sweating, perspiring, because you know you’re going to go out and break the law.”