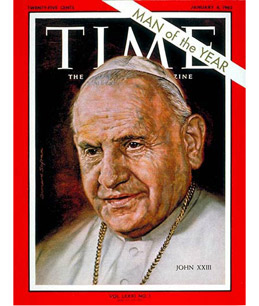

The Year of Our Lord 1962 was a year of American resolve, Russian orbiting, European union and Chinese war. In a tense yet hope-filled time, these were the events that dominated conversation and invited history’s scrutiny. But history has a long eye, and it is quite possible that in her vision 1962’s most fateful rendezvous took place in the world’s most famous church—having lived for years in men’s hearts and minds. That event was the beginning of a revolution in Christianity, the ancient faith whose 900 million adherents make it the world’s largest religion.* It began on Oct. 11 in Rome and was the work of the man of the year. Pope John XXIII, who, by convening the Ecumenical Council called Vatican II, set in motion ideas and forces that will affect not merely Roman Catholics, not only Christians, but the whole world’s ever expanding population long after Cuba is once again libre and India is free of attack. So rare are councils—there have been only 20 in the nearly 2,000 years of Christian history—that merely by summoning Vatican II to “renew” the Roman Catholic Church Pope John made the biggest individual imprint on the year. But revolutions in Christianity are even rarer , and John’s historic mission is fired by a desire to endow the Christian faith with “a new Pentecost,” a new spirit. It is aimed not only at bringing the mother church of Christendom into closer touch with the modern world, but at ending the division that has dissipated the Christian message for four centuries. “The council may have an effect as profound as anything since the days of Martin Luther,” says Dr. Carroll L. Shuster of Los Angeles, an executive of the Presbyterian Church. Boston University’s Professor Edwin Booth, a Methodist and church historian, is so impressed by what Pope John has started that he ranks him as “one of the truly great Popes of Roman Catholic history.” Outranked Concerns. By launching singlehanded a revolution whose sweep and loftiness have caused it to outrank the secular concerns of the year, Pope John created history in a different dimension from that of the most dramatic head line of the year. President Kennedy’s victory over the Russian missile threat in Cuba was both an embarrassing retreat for Khrushchev and a cold war turning point; it showed that a resolute U.S., willing to use its mighty arms, can maintain the initiative in the cold war. There were other big decisions and stunning achievements. In space, the U.S. creditably launched not only John Glenn but Telstar and Mariner II, but it was a team of anonymous Russian scientists who made the year’s biggest space news by lofting the space twins, Nikolayev and Popovich, on record-breaking, three-day tandem orbits of the earth. European unification, both economic and political, rolled along with the dynamism of history . It was symbolized most graphically as Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, the aged and doughty leaders of the New Europe, knelt together at Mass in Reims Cathedral, signifying the burial of ancient antagonisms. On the other side of the world. Communist China’s inscrutable and ruthless leaders launched an attack on neutralist India so seemingly pointless that the big mystery is why they did it at all. The attack embarrassed Russia and further widened the split within Communism that has become an open ideological battle. Mistress of Life. Measured even against such portentous events, the turning point that Christianity reached in 1962 is already assured of a firm place in history, that “mistress of life” to which Pope John occasionally refers. By launching a reform whose goal is to make the Catholic Church sine macula et ruga , John set out to adapt his church’s whole life and stance to the revolutionary changes in science, economics, morals and politics that have swept the modern world: to make it, in short, more Catholic and less Roman. Stretching out the hand of friendship to non-Catholics—he calls them “separated brethren”—he demonstrated that the walls that divide Christianity do not reach as high as heaven, and made a start toward that distant and elusive goal, Christian unity. As a consequence, John XXIII is the most popular Pope of modern times—and perhaps ever. Heading an institution so highly organized that it has been called “the U.S. Steel of churches,” he has demonstrated such warmth, simplicity and charm that he has won the hearts of Catholics, Protestants and non-Christians alike. “The Protestant Christians think that they now have the best Pope they have had in centuries,” comments German Catholic Theologian Herbert Vorgrimler. The Pope’s recent illness raised a tide of concern around the world. “If we should pray for anyone in the world today,” says Protestant Theologian Paul Tillich, “we should pray for Pope John. He is a good man.” John is not only a person of luminous human qualities but an intuitive judge of mankind’s hopes and needs. At first regarded as a transitional Pope who would only warm the chair of Peter, he took over the Catholic Church in 1958 at an age when he was able to leap over the administrative details and parochial interests of the papacy and confront the world as “the universal shepherd.” Unlike his predecessor, the scholarly and aloof Pius XII, John lets his interests range far beyond the Catholic fold to embrace the fundamental plight of man in the modern world. Noble Contest. Last week alone, John demonstrated in the space of a few busy days the qualities that have made him prefer, among all the impressive titles of the Roman Pontiff, the simple designation servus servorum Dei—servant of the servants of God. After delivering a Christmas message in which he rejoiced at the end of the Cuban crisis and pleaded for Christian unity and for peace—”of all the earth’s treasures, the most precious and most noteworthy”—he addressed the 50 ambassadors to the Holy See. “The church,” said John, “applauds man’s growing mastery over the forces of nature and rejoices in all present and future progress which helps men better conceive the infinite grandeur of the Creator.” He also asked support for international bodies such as the United Nations, and urged nations to join in “a noble contest” to explore space and solve economic and social problems. On Christmas Day, John made the first visit outside the Vatican since his illness—to the Bambino Gesu Hospital for children on nearby Janiculum Hill. There he spent 40 minutes walking from ward to ward and speaking personally to almost every child. He talked to them about his own illness. To the doctors and children at Bambino Gesu, he said: “You see, I am in perfect condition. Oh, I am not yet ready to run any races or enter in contests, but in all I am feeling well.” Nonetheless, the feeling persisted in Rome that he is still far from well, and John himself has spoken frequently in recent weeks of the possibility of his imminent death. Only last week he told a group of cardinals: “Our humble life, like the life of everyone, is in the hands of God.” REVOLT IN ST. PETER’S However soon or late that humble life may end, the world will not be able to ignore or forget the forces that Pope John has unleashed. The importance of the council that he called is already clear. By revealing in Catholicism the deep-seated presence of a new spirit crying out for change and rejuvenation, it shattered the Protestant view of the Catholic Church as a monolithic and absolutist system. It also marked the tacit recognition by the Catholic Church, for the first time, that those who left it in the past may have had good cause. “Even the most agnostic and atheistic people were cheered when they saw those thoughtful people saying those thoughtful things,” says one Harvard scientist. Vatican II was the first council called neither to combat heresy, pronounce new dogmas nor marshal the church against hostile forces. As the bishops came to Rome to deliberate, Pope John encouraged “holy liberty” in the expression of their views. The bishops, who had long considered Rome the sole source of power and authority in the Catholic world, gathered together for the first time in their lives, discovered that they and not Rome constituted the leadership of the church. Rome Has Spoken. In its anxiety to defend the doctrines attacked four centuries ago by the Reformation, the Catholic Church had often overemphasized its differences with Protestantism, and had become increasingly dogmatic even about matters that were open topics of discussion before the Reformation—the role of Mary in the church, the role of the sacraments, the infallibility of the Pope. As it reached the Atomic Age, the Catholic Church found itself in perhaps the most powerful condition in its history in terms of numbers, influence and respect—and yet too often still fighting the old battles against Protestantism and “modernism.” The men chiefly responsible for this negative posture belong to the Roman Curia, the central administrative body of the Catholic Church. Mostly aging Italians quite insulated from the modern world, they have exerted vast influence and control not only on the worldwide church but on the Pope himself. They have usually been satisfied with the church the way it is, and have looked upon any efforts to change it with deep hostility. This top-heavy, slow-moving and ultra-conservative body controls all the seminaries that teach young priests, all the church’s missionary activities, all of its ecclesiastical and liturgical legislation. Through the Holy Office, headed by conservative Alfredo Cardinal Ottaviani, the Curia has frequently silenced or harassed Catholic intellectuals, sometimes