Anyone expecting that the U.N.-mandated air campaign over Libya is going to enable the country’s rebels to deliver a knockout blow to the Gaddafi regime ought to visit the front line, around 10 km north of Ajdabiyah. That front line has barely moved in the four days since allied air strikes last weekend destroyed the regime’s armored column that had been advancing on the rebel capital of Benghazi. Although those raids prompted scores of rebel fighters and local war tourists to pile into cars and pickups and surge toward Ajdabiyah, they were quickly repelled by tank shells and Grad rockets fired by Gaddafi’s forces dug in around the town’s northern entrance.

And despite daily tilts at the loyalist positions, always quickly repelled by superior firepower, the stalemate has not been broken. Civilians who have managed to flee the town say regime forces have it under siege and have cut off its water, electricity and cell-phone access — and that they are trying to force civilians to flee.

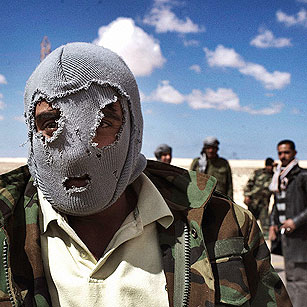

The rebels, largely a mishmash of civilians in military garb, are too poorly armed to dislodge the loyalists. While some are bold enough to drive headlong into loyalist shelling armed with little more than truck-mounted machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades, most of those gathered hang back, waiting for something to move the front line forward.

“We went about three or four kilometers forward at about 3 p.m., but then we came back because they were bombing,” says Ayman Salem, 27, an unemployed worker from Shahat, now clothed in camouflage and perched on a truck alongside an antiaircraft gun. His friends are a 26-year-old mechanic from Benghazi and a 21-year-old day laborer, also from Benghazi. Pointing to his antiaircraft weapon, he says, “There is no comparison between this and Grad missiles.” Although he and his comrades have advanced within range of Gaddafi’s tanks and artillery, they’ve never managed to get close enough to bother firing their truck-mounted gun.

There’s a wide disconnect between the pathos of the rebels gathered north of Ajdabiyah and the tales of grand strategy and steady progress spun by the rebellion’s myriad unofficial spokespeople back in Benghazi. Khaled al-Sayeh, the rebels’ ostensible military spokesman, insists that rebel forces have captured both the eastern and southern gates to Ajdabiyah, bypassing the regime forces dug in at the northern gate by moving along the coast. They have effectively surrounded Gaddafi’s forces and have even begun to encroach on his stronghold of Sirte. Before long, the loyalist forces will run out of ammunition.

At a press conference on Tuesday evening, without so much as glancing at a sheet of paper, al-Sayeh runs off a long list of impressive achievements. In recent days, he says, rebels and allied air forces have destroyed all but 11 of the 80 tanks Gaddafi had sent to Benghazi. Ten other tanks were captured intact, along with 20 pickup trucks, two armored vehicles and a vehicle with radar equipment. He estimates that between 400 and 600 government troops were killed over the weekend.

Giriyani, like al-Sayeh, is part of the ill-defined rebel leadership; a group of men and women, many of them lawyers and businesspeople, who have turned Benghazi’s high court house into the headquarters of Free Libya. Just who heads the Transitional National Council is not entirely clear. They have a functioning media wing and an entourage of spokespeople, but most seem to have little connection to the men out in the desert, fighting — or talking about fighting — this war. The names of three different men have been given over the past three weeks as the ostensible leader of the rebels’ military force. One is Abdel Fatah Younis, Gaddafi’s former Interior Minister, who defected to the rebels’ side. Another is Omar Hariri, a former general who led an unsuccessful revolt against Gaddafi in 1975. And then there is Khalifa Heftir, a famed opposition hero who recently returned from foreign exile to help lead the fight.

On the front line, a few of the volunteers cite Younis as their leader; others say they follow Heftir. Volunteer council translator Shamsiddin Abdulmolah explains it like this: Younis is like the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Heftir is the commander in the field and Hariri is the Defense Minister. But despite these titles, it’s not clear that there’s much of an army to lead.

Some of those fighting in rebel ranks are soldiers who defected from the Libyan army when the east fell to the rebels, but they’re not the majority. And on the desert front lines, they’re often indistinguishable from the teachers, oil workers, laborers and lawyers carrying weapons taken from military bases. And whereas a handful of colonels and a few generals manned the desks on military bases and appeared to oversee some basic weapons training in the first few weeks of Free Libya, few are now seen on the front line. Instead, al-Sayeh says they’re planning and strategizing — he can’t say what exactly — behind the scenes. The task of rallying the disorganized troops at the front has fallen to civilians with megaphones or loud voices.

The loyalists’ rapid advance on Benghazi last week before the coalition air strikes began also shook the fledgling rebel movement. Much of Benghazi’s civilian population has fled to towns farther east, and some of the previously prominent rebel leaders and defecting military commanders appear to have gone to ground. Amid rising fears of fifth columnists and Gaddafi sniper cells amid the loyalist push on the city last Friday and Saturday, some have also grown more suspicious of the soldiers who defected. “The big problem here is that most of the revolutionary guys don’t trust the military people because a lot of military guys were with Gaddafi from the start,” says Najla Elmangoush, a criminal-law professor at Benghazi’s Garyounis University and an activist at council headquarters. “We welcomed them when they joined,” she adds. “But people are concerned that maybe they’ll try anytime to change sides.” The regime is trying to encourage that fear, spreading false rumors last weekend that rebel commander Younis had returned to the regime’s camp.

Even though the intervention by allied air forces has saved Benghazi from being overrun by Gaddafi’s forces, the state of the rebels’ military there, and down the road on the approaches to Ajdabiyah, suggests it may be quite some time before they’re ready to march on Tripoli.

Read “Libya’s Rebels: Taking the Fight to Gaddafi, with Help.”

See pictures of the battle for Libya.