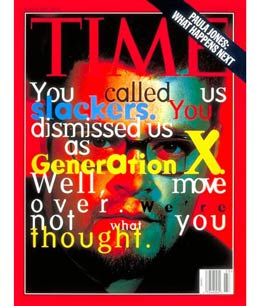

Who would have thought the kids would start taking over so soon? Or that they would even want to? They were supposed to be slackers, cynics, drifters. But don’t be fooled by their famous pose of repose. Lately, more and more of them are prowling tirelessly for the better deal, hunting down opportunities that will free them from the career imprisonment that confined their parents. They are flocking to technology start-ups, founding small businesses and even taking up causes–all in their own way. They are making waves on the Web, making movies in and out of Hollywood, making money, spending money. Slapped with the label Generation X, they’ve turned the tag into a badge of honor. They are X-citing, X-igent, X-pansive. They’re the next big thing. Boomers, beware! It’s payback time. A few months ago, a prominent polling firm teamed up with a major advertising agency to undertake a comprehensive survey comparing three generations. They interviewed hundreds of twentysomethings from Big Sandy, Tenn., to Oak Lawn, Ill., to Riverside, Calif. They talked to scores of fortysomethings and sixtysomethings. Now, exclusively in TIME, the New American Dream study is ready for release. News flash! The youngsters are ambitious get-aheads–even more so than their parents or grandparents. They are confident, savvy and, the survey concludes with a measure of relief, materialistic. “Gen X is committed,” enthuses J. Walker Smith, managing partner at the polling firm Yankelovich Partners. “Gen X is connected. Gen X craves success American-style.” So what happened to those lazy, listless baby busters who supposedly typified the new generation? Beavis and Butt-head were their icons; Beck’s Loser was their song ; Richard Linklater’s Slacker, with its Austin, Texas, deadbeats, was their movie. This was the MTV generation: Net surfing, nihilistic nipple piercers whining about McJobs; latchkey legacies, fearful of commitment. Passive and powerless, they were content, it seemed, to party on in a Wayne’s Netherworld, one with more antiheroes–Kurt Cobain, Dennis Rodman, the Menendez brothers–than role models. The label that stuck was from Douglas Coupland’s 1991 novel, Generation X, a tale of languid youths musing over “mental ground zero–the location where one visualizes oneself during the dropping of the atomic bomb: frequently a shopping mall.” Whatever. Albeit overshadowed by 78 million self-important boomers, the 45 million Xers born between 1965 and 1977 represent $125 billion in annual purchasing power a year. And of late, reading their psyches has become less a genteel academic pastime than an extreme sport in which sneakermakers, brewers and car manufacturers scramble for market share. Politicians trolling for votes, churches seeking converts, military services recruiting soldiers, moviemakers looking for viewers and magazines for readers: hardly a sliver of society is exempt from the need to understand and, indeed, cater to this generation. Yet Gen X has proved irritatingly contrarian. “The soul of Gen X is amorphous, intangible, elusive,” says Richard Thau, 32, who heads the civic group Third Millennium. “That’s why I like the term X: fill in the blanks.” So convincing were the early stereotypes that three years ago, Coca-Cola, targeting teens and Gen Xers, test-marketed a new drink called OK soda. The gray cans featured grim designs, including one of a doleful youth slumped outside two idle factories. Slogans on the cans read, “Don’t be fooled into thinking there has to be a reason for everything” and “What’s the point of OK soda? Well, what’s the point of anything?” The nine-city campaign fizzled. And the company that a quarter-century ago had celebrated the baby boom with the jingle, “I’d like to teach the world to sing,” killed the product. Meanwhile, a grunge-themed Subaru campaign that told viewers its cars were “like punk rock” fell flat, and Converse was surprised to find that Gen Xers were put off by a spot showing an All Star-shod youth spray-painting his name on a building. Today forecasters, salesmen and pundits–many the middle-age parents of perplexing offspring–are acknowledging that their first X rays of the new generation were distorted. “The baby boomers of the media and marketing world were desperate to explain a generation they didn’t understand, so they reduced Xers to a cartoon,” says Adam Morgan, managing partner at TBWA Chiat/Day, the ad agency that collaborated with Yankelovich. “It may be the most expensive marketing mistake in history.” Last year the magazine Who Cares and the Center for Policy Alternatives, a Washington think tank, released a survey that showed 72% of 18-to-24-year-olds believe this generation “has an important voice, but no one seems to hear it.” Asked how older generations viewed them, their top answers were “lazy,” “confused” and “unfocused.” Asked how they saw themselves, they replied “ambitious,” “determined” and “independent.” XERS, BOOMERS, MATURES A generation is forged through common experience. The cohort described as “matures,” born from 1909 to 1945, was shaped by the Depression and World War II. “Boomers,” born from 1946 to 1964, grew up in affluence: economic progress was assumed, freeing them to focus on idealism and personal growth. Young Xers, however, lurched through the recession of the early ’80s, only to see the mid-decade glitz dissipate in the 1987 stock-market crash and the recession of 1990-91. Gen X could never presume success. In their new book Rocking the Ages, Yankelovich’s Smith and his colleague Ann Clurman blame Xers’ woes on their parents: “Forget what the idealistic boomers intended, Xers say, and look instead at what they actually did: divorce. Latchkey kids. Homelessness. Soaring national debt. Bankrupt Social Security. Holes in the ozone layer. Crack. Downsizing and layoffs. Urban deterioration. Gangs. Junk bonds…”