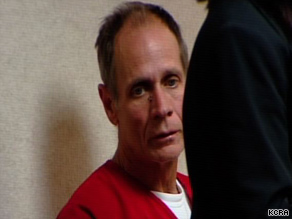

Phillip Garrido was registered as a sex offender, required to meet with parole officers and fitted with an ankle bracelet to track his movements — but nothing prevented him from being around children, according to a victim’s advocacy group.

Garrido, who is charged with kidnapping and raping Jaycee Lee Dugard — a young woman police say lived with her two daughters in a huddle of tents and outbuildings hidden behind Garrido’s home – was arrested last week along with his wife Nancy. Both have pleaded not guilty. Dugard grew up in the compound and raised the girls, now 11 and 15, that she bore and Garrido fathered, police said. Dugard was abducted in 1991 at age 11. “Here we have a guy who is essentially under every kind of supervision we allow. Law enforcement had every tool available to them, and [the tools] failed,” said Robert Coombs, spokesman for the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Garrido “was technically allowed to be around minors,” Coombs said, because his parole stemmed from the November 1976 rape of Katie Callaway Hall, who was 25 at the time of the assault. He was sentenced in 1977 to 50 years at the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, for kidnapping because he abducted Hall in California and transported her across the state line to Reno, Nevada, where he raped her in a warehouse, according to court documents. A Nevada court separately sentenced him to five years to life for the rape conviction, the Reno-Gazette Journal reported. While in prison in 1978, Garrido sent a handwritten letter to Judge Bruce R. Thompson, saying he was recovering from seven years of LSD use and progressing well. “I am so ashamed of my past. But my future is now in controle [sic],” he wrote. Court documents show Garrido requested that his 50-year sentence be reduced to 25, making him eligible for parole in eight years, “where he could be released to the state of Nevada as an educated person and being a rehabilitated person.” According to a 1978 court transcript, attorney Willard Van Hazel Jr. told a judge, “Without the influence of any of this drug involvement, I think Mr. Garrido would pause before carrying out sexual fantasies.”

Don’t Miss

Authorities study bone found near accused kidnapper’s home

Officers who cracked case: Something wasn’t right

Abductee’s daughters’ lives seemed normal, friend says

Alleged kidnapper couple met while man was in prison

After more than a decade at Leavenworth, Garrido received a federal parole but was sent to Carson City, Nevada, in January 1988 to serve his rape sentence. However, according to the Reno Gazette-Journal, he was automatically eligible for state parole because of the time served in federal prison. The Nevada Offender Tracking Information System indicates he went four times before the parole board, which granted his request in August 1988, about 11 years after he was incarcerated. He moved to Antioch, California, where authorities said they learned Dugard, now 29, had been living in the backyard since her abduction. “He served about 20 percent of his sentence, and it doesn’t take a mathematician to figure out if he served only one-third of his sentence, Jaycee Dugard doesn’t end up in the predicament that she’s in,” said Andy Kahan, crime victim’s advocate in Houston, Texas. Citing revised federal sentencing guidelines, Kahan and Illinois defense attorney Stephen Komie concur that this is not something that could happen today. “If he got 50 years, say, he would have 600 months. He would only get 50 months off. He would do 550 months,” Komie said. “So this would not be repeated in the federal system again.” Added Kahan, “You’re going to have to do at least a minimum of half of your term without any good time credits before you can even see the light of day or say hello to a parole board member.” In 1993, five years after his release from a Nevada prison, Garrido was jailed on a parole violation, but it’s unclear what that offense was. Tom Hutchinson, spokesman for the U.S. Parole Commission, said documents have been requested and should be available later this week. Garrido was released later that year. The California Coalition Against Sexual Assault’s Coombs said Garrido was required to meet regularly with parole officers, who unearthed nothing about Dugard’s abduction or Garrido’s backyard secrets. Another visit by law enforcement was the direct result of a 2006 call a neighbor made to 911, reporting that women and children were living in tents behind Garrido’s house. Contra Costa County Sheriff Warren E. Rupf said he didn’t think the deputy knew Garrido was a sex offender at the time and spoke to Garrido in the home’s front yard. “We should have been more inquisitive, more curious and turned over a rock or two,” the sheriff said. “We missed an opportunity to bring earlier closure to this situation.” Kahan partially blames the economics of the criminal justice system – not just in California, but nationwide — and said Garrido likely became less of a priority as the time since his crimes passed. Despite the heinous nature of Garrido’s 1976 crime, it paled to allegedly holding a young girl hostage and raping her for 18 years, Coombs said. “Nothing in this guy’s case history indicated he was capable of such evil, if you will,” he said. “It was so far out of the picture, they didn’t even look for it.” Rather than there not being enough money to fund the proper supervision of parolees, it’s more a matter of priorities, Coombs said, citing the global-positioning system Garrido wore on his ankle. Although CALCASA has no official tally, it estimates California spends roughly $500 million a year on GPS devices for 6,600 of the state’s sex offenders. Garrido was fitted with a device after California voters passed Jessica’s Law in November 2006. Each dollar spent on GPS equipment “is one dollar you’re not spending on real, traditional parole techniques, like talking to collateral contacts and neighbors,” he said.

Had Garrido’s parole officer spoken to the neighbor who made the 911 call in 2006, authorities might have found Dugard three years earlier, Coombs said. “We know where this guy is, so we think we’re safe,” he said, “but the place where we knew he was was the place where he was offending. GPS just tells you where they are. It doesn’t tell you what they’re doing.”