Early on in his newly released memoir, George W. Bush writes with great credibility, and a welcome absence of histrionics, about his slow-motion turn toward faith. There was no fiery epiphany. There was a growing comfort with the calming release of prayer, a gradual appreciation of the moral truths contained in the Bible. There were doubts too. “If you haven’t doubted, you probably haven’t thought very hard about what you believe,” he writes. And that principle is very much in evidence when he makes the first major decision of his presidency, in favor of federal funding for research on existing stem-cell lines but not for raiding frozen embryos — potential lives, he believes — to harvest their cells. To reach that decision, Bush conducted a White House seminar that included talks with advocates, brilliant ones, on all sides of the issue. “The conversations fascinated me,” he writes. “The more I learned, the more questions I had.” Whatever you think of his policy, the process was impeccable.

I mention this not only because it reveals Bush at his best but because it was so much at variance with the rest of his presidency.

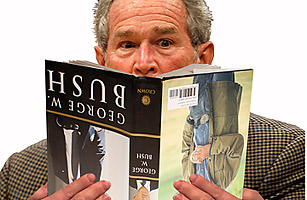

The presidential memoir is among the more dreadful of literary forms. Most of them are far too long, and suffocating for the heavy woolen tone of false modesty that swaddles the egomania at the heart of the matter. They are defensive, evasive and stiff. Bush’s effort is all that, but better than most. It reads well. The anecdotes are occasionally revealing. There is emotion, and it is real. The pace is brisk enough to delude the unwary reader into a suspension of disbelief at first, but gradually the weakness of this chatty strategy becomes clear: Bush breezes through fundamental and earth-shattering decisions without slowing down to acknowledge their moral complexity. At the most important moments of his presidency — most notably, the decision to go to war in Iraq — he refuses to honestly consider opposing points of view or see the long-term, ancillary effects of what he is deciding.

Some of the decisions he makes are wise, like the belated move toward a counterinsurgency strategy in Iraq. In other cases, like Hurricane Katrina, he successfully defends his efforts and candidly acknowledges his mistakes. But as the pages turn, a familiar sense of the man unfurls: impatient, petulant, shallow — quite the opposite of the stem-cell decider. Bush writes that his true feelings as he found out about the 9/11 attacks — and chose to sit, famously impassive, as a Florida class read “The Pet Goat” — were, “My blood was boiling. We were going to find out who did this, and kick their ass.” It was an understandable reaction, but an emotion he never quite transcended or transformed into strategic thought.

In the book, Bush never stops to wonder if, maybe, his team should have spent more time focusing on al-Qaeda before Sept. 11 — as the outgoing Clinton national-security team had strongly suggested — or whether he should have taken more seriously the infamous Aug. 6, 2001, memo from the CIA warning of an al-Qaeda attack on the homeland. And later, he never stops to wonder if the U.N. inspectors, whom Saddam Hussein had allowed back into Iraq, were not finding weapons of mass destruction because, maybe, uh, the WMD didn’t exist. And still later, he expresses shock at the Abu Ghraib abuses without ever admitting — or, perhaps, finding out — that practices like enforced nudity, the use of dogs and stress positions had become common. And of course he never acknowledges the subsequent reporting, by multiple news outlets, that proved Abu Ghraib was different from other interrogation sites only in that photos were taken. In a particularly appalling moment, Bush simply decides to permit waterboarding enemy detainees because, as he told Matt Lauer, “the lawyer said it was legal.”