An Australian high court ruled Friday that a quadriplegic man has the right to refuse food and water and can be allowed to die, a rare legal finding that some see as a major victory for right-to-die campaigners.

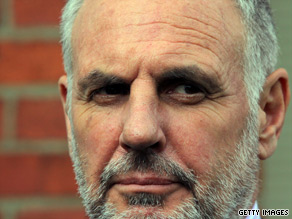

The ruling means that the nursing facility in which Christian Rossiter has lived since November 2008 cannot be held criminally liable for allowing the patient to die, the Supreme Court of Western Australia said. “I’m happy that I won my right to die,” Rossiter, 49, said afterward. But he added that he will further consult with a doctor because he may change his mind. A leading Australian right-to-die advocate called the ruling a significant victory. “I don’t know that many people will want to die this way. But for people who do, it’s a very important decision,” said Dr. Philip Nitschke, founder and director of Exit International, a leading global voluntary euthanasia and end-of-life advocacy group. Nitschke noted that Rossiter’s case is significant because his mind is fully functional. “This is the first time that it’s come up with a person that’s rational and lucid,” Nitschke told CNN. “This is unusual. It’s very rare.” Chief Justice Wayne Martin noted that distinction in his order, saying, “Mr. Rossiter is not a child, nor is he terminally ill, nor dying. He is not in a vegetative state, nor does he lack the capacity to communicate his wishes. There is therefore no question of other persons making decisions on his behalf. “Rather, this is a case in which a person with full mental capacity and the ability to communicate his wishes has indicated that he wishes to direct those who have assumed responsibility for his care to discontinue the provision of treatment which maintains his existence.” Some family and right-to-life groups opposed Rossiter’s request. “Really, what we should be doing is looking after each other rather than facilitating an escape,” John Barich of the Australian Family Association said in a TV interview.

Don’t Miss

UK legal victory for assisted suicide campaign

MS sufferer challenges suicide ruling

Peter O’Meara, president of Western Australia’s Right to Life Association, said, “The law which is being applied can be a dangerous precedent.” Rossiter has suffered a series of injuries since 1988 that have left him with limited foot movement and the ability to wriggle only one finger. He is fed through a stomach tube. He relies on staff at the Brightwater Care Group nursing facility in the city of Perth for such routine care as regular turning, cleaning, assistance with bowel movements, physical and occupational therapy and speech pathology. Australian law gives patients the right to refuse life-saving treatment, but helping someone commit suicide is a crime that can carry a life prison sentence. The Brightwater nursing facility sought the ruling to make sure it would not be held liable if it complied with Rossiter’s request to stop all nutrition and hydration, except to be given enough liquid to make it possible to take pain medication. Rossiter attended the hearing in a wheelchair, breathing through a tracheotomy tube in his throat. He told the judge he wants to die. It’s a point he has been making publicly. “I can’t move,” Rossiter said in a televised interview this week. “I can’t even wipe the tears from my eyes. And I’d like to die. I’m imprisoned in my own body. I have no fear of death. Just pain.” Rossiter pointed out in a recent interview with the PerthNow news outlet that he once led an active life. “This is living hell,” he is quoted as saying. “I used to be a cyclist, I used to be a keen walker. I bushwalked around the world. … I’ve rock climbed in Yosemite Valley in California up very steep cliffs. I’ve got a degree in economics and now I can’t even read a newspaper, I can’t turn the pages.” Rossiter joined the Exit International right-to-death organization about three months ago, said Nitschke, who talked with him before the hearing. Nitschke said Rossiter appeared “very happy” afterward. A Brightwater executive said the company appreciates that the court’s ruling has relieved the nursing facility of any liability. “The whole organization has been most concerned for Mr. Rossiter but also concerned for our own legal standing and this has clarified things greatly,” said Penny Flett, the company’s chief executive. While hailing the victory, Nitschke decried the fact that Rossiter will have to undergo a slow and painful death through starvation, rather than having a quicker and painless way to end his life. Because he cannot use his hands, Rossiter must rely on others to withhold treatment rather than being able to take his own life. Switzerland has an assisted suicide law, and Rossiter has considered going there. “It’s a bit sad that the best that Australia can come up with,” Nitschke said, “is that we can let a person like that starve to death.”