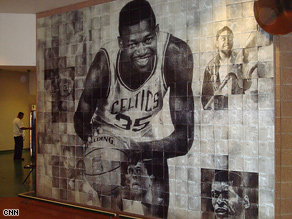

A huge mural greets visitors to the Reggie Lewis Track and Athletic Center in Boston. It’s a memorial to the building’s namesake, who died unexpectedly in 1993.

A young Reggie Lewis, wearing his No. 35 Boston Celtics jersey, dominates the middle of the 11-foot-by-14-foot artwork. At the bottom left is a picture of him and his wife. To his right, the face of legendary Celtic Larry Bird. But as young men in sweats and sneakers make their way into the gym, something strange happens. The mural comes alive. The photo of a beaming Lewis in formal attire transforms into Lewis the basketball player, streaking down the court. Larry Bird’s picture morphs into that of another famous player, Robert Parrish. With each step, the mural transforms, representing the many scenes in one man’s life. Artist Rufus B. Seder calls these “movies for a wall” Lifetiles. The Massachusetts artist invented the Lifetiles medium and is the only artist in the world using it. He has more than 30 Lifetiles installations around the globe. Watch a magic mural in action » At the Taiwan Aquarium, dolphins swim on the wall alongside awestruck children. Bucking broncos line the halls of the the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas. Dancers spin and twirl along with passengers on luxury cruise ships in the south of France. And Seder calls the the South San Francisco, California, BART station his “own personal gallery,” with more than 16 installations. Lifetiles don’t use electricity, moving parts or tricky lighting — just an elaborate and painstaking process done out of Seder’s Eye Think Inc. studio near Boston. “What I’m after is trying to create an experience which totally takes you by surprise,” he said. Scanimation on the shelf

Don’t Miss

In Depth: Edge of Discovery

Floating city could be just 3 years away

Winged luxury submarines ‘fly’ underwater

If the technology you see in Lifetiles looks familiar, you might have caught something similar at a local bookstore. The popular children’s books “Gallop!” and “Swing!” were also written and illustrated by Seder. With a technique he calls scanimation, pictures in the books come alive as you flip the page. It’s a kids’ favorite that quite a few parents enjoy, too, based on sales numbers. “Swing!” and “Gallop!” are currently on The New York Times bestseller list. Seder originally used scanimation in greeting cards he sold at trade shows around the country. Then Workman Publishing came calling, asking Seder to develop a book based on the eye-catching technique. That’s when Seder caught lightning in a bottle. After several decades as a somewhat unknown artist, he found himself flying to China to teach the scanimation technique to book makers. Just a few years later, there are over 2 million copies of “Gallop!” in print in more than 13 languages. Still awed by their popularity, Seder said, “I would’ve been satisfied if a limited edition sold well. It totally blew my mind what happened.” Although his books’ success have gained Seder some newfound publicity, the Lifetiles are truly his life’s work. The relatively unknown and seemingly modern form of art isn’t new at all. Seder’s been working on Lifetiles for more than 20 years, inspired by toys from the 1850s called zoetropes and an active imagination as a youngster. “I started making movies when I was 12 years old,” he said, “so I was always into motion pictures and especially into optical tricks and techniques that trick the eye.” How does it work As a viewer, you don’t have to learn how to see a Lifetile. It’s intuitive, and one immediately understands the concept. As you walk past the mural, it begins to move along with you. But the question that immediately comes to mind — and the one Seder gets the most — is, “How does it work” “The short answer is, it’s magic,” Seder said. “The longer answer is, it’s like a flipbook. I’ve taken all the pages from a flipbook and scrambled them all together, and I’ve put them up on the wall and made them animate.” The lengthy process also requires attention to detail. Much like an animator, he creates a series of drawings on his computer. He then strips down each image into what becomes an indistinguishable picture made up of a series of vertical lines. This squiggly-lined image becomes the equivalent of a photo negative. The negative gets sandblasted onto a hand-cast glass tile made in Seder’s studio. The heavy, 8-inch-square glass tiles get painted, scraped, fired in a kiln and finally added piece by piece to a Lifetiles mural. Hundreds of these tiles work in harmony to create a huge moving image when displayed on a wall. Seder patented the painstaking technique but thinks most other artists wouldn’t have his patience, even if they had his know-how. “It’s not that I’ve been playing my cards close to my vest,” he said. “It’s just very difficult to do.”

A Lifetiles installation, from conception to completion, can take up to a year to complete. It’s a labor of love he shares with others who walk by his “magic” walls. “I love to watch people react to the work. They don’t expect a wall to move,” he said. “They’ll be walking down the hallway in a museum and walking outdoors through a zoo … and suddenly they realize, ‘Those dolphins are starting to move next to me! How is that possible’ ”