This is the tale of the enmity of three women: the first is perhaps the richest in Argentina; the second is the President of the country; the third, a grandmother in search of the children of desaparecidos, the 30,000 or so mostly young people who disappeared in the military junta’s death camps from 1976 to 1983. The objects of their contention are two adopted children, a brother and sister, who stand to inherit an immense fortune — or see it shrink, if their genes betray a past that might help dramatically diminish their mother’s business empire.

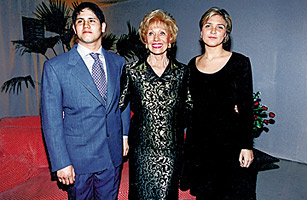

Marcela and Felipe Noble Herrera, both 34, were adopted in 1976 by Ernestina Herrera de Noble, the owner of the media conglomerate Clarn, which holds hugely influential and profitable properties, including the newspaper that is said to have the largest circulation in the Hispanic world, the most visited Spanish-language news website and a vast television, cable and radio empire. Goldman Sachs has an 18% stake in Clarn, which Noble grew to its prodigious proportions after the death of her newspaper-publisher husband Roberto Noble in 1969. Now 84, she is estimated to be worth $1 billion. Marcela and Felipe are her only heirs.

Clarn has been a harsh critic of the administration of President Cristina Fernndez de Kirchner, with the conglomerate being particularly focused on allegations of corruption. The President was personally incensed by a 2008 cartoon in the newspaper Clarn that depicted her with an X taped across her mouth. Alluding to the country’s traumatic military rule, she decried the cartoon as a “mafia-like message” from “media generals” who were plotting her overthrow. Last year, the government sent an army of 200 tax inspectors into Clarn offices to investigate the company’s books; they found no irregularities. More ominous, when the President’s Peronist party still held a majority, the country’s congress passed a media-monopoly law to try to break up Noble’s television and cable holdings by placing a limit on the number of cable companies and channels one corporation could hold in cities and provinces. How soon the law actually gets implemented is in the hands of Argentina’s supreme court.

Perhaps unwittingly, coming to the President’s aid is Estela de Carlotto, the head of Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo , a human-rights group that since the end of the military dictatorship in 1983 has located and identified through DNA testing 101 children who were born in Argentina’s death camps to female political activists. The country’s junta allowed pregnant detainees to live only long enough to give birth, after which the mothers were murdered and the infants handed over to military families to raise as their own. In a small number of cases, the newborns were given to unknowing civilian families for adoption. Carlotto, who has been searching for her own grandson for decades, believes Marcela and Felipe were born in the camps; Abuelas has sued their adoptive mother to find out for certain.

If Marcela and Felipe are indeed the offspring of prisoners, and if Noble’s enemies can dig up evidence that she knew they had been born in the camps, then she may be charged with what Argentine laws call crimes against humanity. At least one prominent member of the government is already alleging that part of her empire, specifically involving the newsprint company Papel Prensa, was built in collusion with the junta. If substantiated, this additional assault on Clarn may help the Fernandez administration break up Noble’s empire by alleging criminality at its inception. Argentina’s new Foreign Minister, Hector Timmerman, was ecstatic at the possibility. Two weeks ago, in Washington, where he was finishing his stint as the country’s ambassador to the U.S., Timmerman tweeted, “Media law, done. Papel Prensa, almost there. Origin of Felipe and Marcela, any moment now.” Carlotto, however, says she wants only to see justice done. “For Abuelas, this is not a fight between the government and a newspaper,” she said earlier this year. “I ask Mrs. Noble to free the children so they can think for themselves.”

The trouble is that Marcela and Felipe have provided their DNA three times already. The first time, they did so voluntarily, cooperating with court forensic experts in December. Court experts later confiscated toothbrushes and other materials from their home and, most dramatically, on May 28, after police chased them home after a court appearance. On that day, law-enforcement officials armed with a warrant raided their mother’s house in the Buenos Aires suburb of San Isidro and forced Marcela and Felipe to strip and hand over all their clothing, including underwear, to obtain DNA samples. A source who witnessed the police chase says the experience was traumatic for the siblings. “Felipe burst out crying in front of the police when he was forced to undress,” says the source. “Marcela was also forced to undress, in a separate room in front of seven people, and then taken to a bathroom with two officers, where she was made to take off and hand over her underwear.”

“We are treated like criminals, though we have committed no crime,” Marcela and Felipe said in a prepared statement after the police raid. To make matters worse, the clothes seized on May 28 held traces of DNA from at least three different people, making it impossible to map DNA profiles for the siblings. The previous blood sample was rejected by Abuelas because the group believes the process was open to possible tainting. There have been documented cases of this in the past, which is why Abuelas will take only samples handled by the National Genetic Data Bank , which holds the DNA information from the families of about 500 missing children. The Noble Herreras, however, do not trust the BNDG, because it is in the direct orbit of the office of President Fernandez. So the DNA collected in December remains unexamined.

See the top 10 crime stories of 2009.

See the top 10 news stories of 2009.